Appendix A: Advanced Prompting Techniques

Introduction to Prompting

Prompting, the primary interface for interacting with language models, is the process of crafting inputs to guide the model towards generating a desired output. This involves structuring requests, providing relevant context, specifying the output format, and demonstrating expected response types. Well-designed prompts can maximize the potential of language models, resulting in accurate, relevant, and creative responses. In contrast, poorly designed prompts can lead to ambiguous, irrelevant, or erroneous outputs.

The objective of prompt engineering is to consistently elicit high-quality responses from language models. This requires understanding the capabilities and limitations of the models and effectively communicating intended goals. It involves developing expertise in communicating with AI by learning how to best instruct it.

This appendix details various prompting techniques that extend beyond basic interaction methods. It explores methodologies for structuring complex requests, enhancing the model’s reasoning abilities, controlling output formats, and integrating external information. These techniques are applicable to building a range of applications, from simple chatbots to complex multi-agent systems, and can improve the performance and reliability of agentic applications.

Agentic patterns, the architectural structures for building intelligent systems, are detailed in the main chapters. These patterns define how agents plan, utilize tools, manage memory, and collaborate. The efficacy of these agentic systems is contingent upon their ability to interact meaningfully with language models.

Core Prompting Principles

Core Principles for Effective Prompting of Language Models:

Effective prompting rests on fundamental principles guiding communication with language models, applicable across various models and task complexities. Mastering these principles is essential for consistently generating useful and accurate responses.

Clarity and Specificity: Instructions should be unambiguous and precise. Language models interpret patterns; multiple interpretations may lead to unintended responses. Define the task, desired output format, and any limitations or requirements. Avoid vague language or assumptions. Inadequate prompts yield ambiguous and inaccurate responses, hindering meaningful output.

Conciseness: While specificity is crucial, it should not compromise conciseness. Instructions should be direct. Unnecessary wording or complex sentence structures can confuse the model or obscure the primary instruction. Prompts should be simple; what is confusing to the user is likely confusing to the model. Avoid intricate language and superfluous information. Use direct phrasing and active verbs to clearly delineate the desired action. Effective verbs include: Act, Analyze, Categorize, Classify, Contrast, Compare, Create, Describe, Define, Evaluate, Extract, Find, Generate, Identify, List, Measure, Organize, Parse, Pick, Predict, Provide, Rank, Recommend, Return, Retrieve, Rewrite, Select, Show, Sort, Summarize, Translate, Write.

Using Verbs: Verb choice is a key prompting tool. Action verbs indicate the expected operation. Instead of “Think about summarizing this,” a direct instruction like “Summarize the following text” is more effective. Precise verbs guide the model to activate relevant training data and processes for that specific task.

Instructions Over Constraints: Positive instructions are generally more effective than negative constraints. Specifying the desired action is preferred to outlining what not to do. While constraints have their place for safety or strict formatting, excessive reliance can cause the model to focus on avoidance rather than the objective. Frame prompts to guide the model directly. Positive instructions align with human guidance preferences and reduce confusion.

Experimentation and Iteration: Prompt engineering is an iterative process. Identifying the most effective prompt requires multiple attempts. Begin with a draft, test it, analyze the output, identify shortcomings, and refine the prompt. Model variations, configurations (like temperature or top-p), and slight phrasing changes can yield different results. Documenting attempts is vital for learning and improvement. Experimentation and iteration are necessary to achieve the desired performance.

These principles form the foundation of effective communication with language models. By prioritizing clarity, conciseness, action verbs, positive instructions, and iteration, a robust framework is established for applying more advanced prompting techniques.

Basic Prompting Techniques

Building on core principles, foundational techniques provide language models with varying levels of information or examples to direct their responses. These methods serve as an initial phase in prompt engineering and are effective for a wide spectrum of applications.

Zero-Shot Prompting

Zero-shot prompting is the most basic form of prompting, where the language model is provided with an instruction and input data without any examples of the desired input-output pair. It relies entirely on the model’s pre-training to understand the task and generate a relevant response. Essentially, a zero-shot prompt consists of a task description and initial text to begin the process.

- When to use: Zero-shot prompting is often sufficient for tasks that the model has likely encountered extensively during its training, such as simple question answering, text completion, or basic summarization of straightforward text. It’s the quickest approach to try first.

- Example:

Translate the following English sentence to French: ‘Hello, how are you?’

One-Shot Prompting

One-shot prompting involves providing the language model with a single example of the input and the corresponding desired output prior to presenting the actual task. This method serves as an initial demonstration to illustrate the pattern the model is expected to replicate. The purpose is to equip the model with a concrete instance that it can use as a template to effectively execute the given task.

- When to use: One-shot prompting is useful when the desired output format or style is specific or less common. It gives the model a concrete instance to learn from. It can improve performance compared to zero-shot for tasks requiring a particular structure or tone.

-

Example:

Translate the following English sentences to Spanish:

English: ‘Thank you.’

Spanish: ‘Gracias.’English: ‘Please.’

Spanish:

Few-Shot Prompting

Few-shot prompting enhances one-shot prompting by supplying several examples, typically three to five, of input-output pairs. This aims to demonstrate a clearer pattern of expected responses, improving the likelihood that the model will replicate this pattern for new inputs. This method provides multiple examples to guide the model to follow a specific output pattern.

- When to use: Few-shot prompting is particularly effective for tasks where the desired output requires adhering to a specific format, style, or exhibiting nuanced variations. It’s excellent for tasks like classification, data extraction with specific schemas, or generating text in a particular style, especially when zero-shot or one-shot don’t yield consistent results. Using at least three to five examples is a general rule of thumb, adjusting based on task complexity and model token limits.

- Importance of Example Quality and Diversity: The effectiveness of few-shot prompting heavily relies on the quality and diversity of the examples provided. Examples should be accurate, representative of the task, and cover potential variations or edge cases the model might encounter. High-quality, well-written examples are crucial; even a small mistake can confuse the model and result in undesired output. Including diverse examples helps the model generalize better to unseen inputs.

- Mixing Up Classes in Classification Examples: When using few-shot prompting for classification tasks (where the model needs to categorize input into predefined classes), it’s a best practice to mix up the order of the examples from different classes. This prevents the model from potentially overfitting to the specific sequence of examples and ensures it learns to identify the key features of each class independently, leading to more robust and generalizable performance on unseen data.

- Evolution to “Many-Shot” Learning: As modern LLMs like Gemini get stronger with long context modeling, they are becoming highly effective at utilizing “many-shot” learning. This means optimal performance for complex tasks can now be achieved by including a much larger number of examples—sometimes even hundreds—directly within the prompt, allowing the model to learn more intricate patterns.

-

Example:

Classify the sentiment of the following movie reviews as POSITIVE, NEUTRAL, or NEGATIVE:Review: “The acting was superb and the story was engaging.”

Sentiment: POSITIVEReview: “It was okay, nothing special.”

Sentiment: NEUTRALReview: “I found the plot confusing and the characters unlikable.”

Sentiment: NEGATIVEReview: “The visuals were stunning, but the dialogue was weak.”

Sentiment:

Understanding when to apply zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot prompting techniques, and thoughtfully crafting and organizing examples, are essential for enhancing the effectiveness of agentic systems. These basic methods serve as the groundwork for various prompting strategies.

Structuring Prompts

Beyond the basic techniques of providing examples, the way you structure your prompt plays a critical role in guiding the language model. Structuring involves using different sections or elements within the prompt to provide distinct types of information, such as instructions, context, or examples, in a clear and organized manner. This helps the model parse the prompt correctly and understand the specific role of each piece of text.

System Prompting

System prompting sets the overall context and purpose for a language model, defining its intended behavior for an interaction or session. This involves providing instructions or background information that establish rules, a persona, or overall behavior. Unlike specific user queries, a system prompt provides foundational guidelines for the model’s responses. It influences the model’s tone, style, and general approach throughout the interaction. For example, a system prompt can instruct the model to consistently respond concisely and helpfully or ensure responses are appropriate for a general audience. System prompts are also utilized for safety and toxicity control by including guidelines such as maintaining respectful language.

Furthermore, to maximize their effectiveness, system prompts can undergo automatic prompt optimization through LLM-based iterative refinement. Services like the Vertex AI Prompt Optimizer facilitate this by systematically improving prompts based on user-defined metrics and target data, ensuring the highest possible performance for a given task.

- Example:

You are a helpful and harmless AI assistant. Respond to all queries in a polite and informative manner. Do not generate content that is harmful, biased, or inappropriate

Role Prompting

Role prompting assigns a specific character, persona, or identity to the language model, often in conjunction with system or contextual prompting. This involves instructing the model to adopt the knowledge, tone, and communication style associated with that role. For example, prompts such as “Act as a travel guide” or “You are an expert data analyst” guide the model to reflect the perspective and expertise of that assigned role. Defining a role provides a framework for the tone, style, and focused expertise, aiming to enhance the quality and relevance of the output. The desired style within the role can also be specified, for instance, “a humorous and inspirational style.”

- Example:

Act as a seasoned travel blogger. Write a short, engaging paragraph about the best hidden gem in Rome.

Using Delimiters

Effective prompting involves clear distinction of instructions, context, examples, and input for language models. Delimiters, such as triple backticks (\`\`\`), XML tags (\<instruction\>, \<context\>), or markers (—), can be utilized to visually and programmatically separate these sections. This practice, widely used in prompt engineering, minimizes misinterpretation by the model, ensuring clarity regarding the role of each part of the prompt.

- Example:

<instruction>Summarize the following article, focusing on the main arguments presented by the author.</instruction>

<article>

[Insert the full text of the article here]

</article>

Contextual Enginnering

Context engineering, unlike static system prompts, dynamically provides background information crucial for tasks and conversations. This ever-changing information helps models grasp nuances, recall past interactions, and integrate relevant details, leading to grounded responses and smoother exchanges. Examples include previous dialogue, relevant documents (as in Retrieval Augmented Generation), or specific operational parameters. For instance, when discussing a trip to Japan, one might ask for three family-friendly activities in Tokyo, leveraging the existing conversational context. In agentic systems, context engineering is fundamental to core agent behaviors like memory persistence, decision-making, and coordination across sub-tasks. Agents with dynamic contextual pipelines can sustain goals over time, adapt strategies, and collaborate seamlessly with other agents or tools—qualities essential for long-term autonomy. This methodology posits that the quality of a model’s output depends more on the richness of the provided context than on the model’s architecture. It signifies a significant evolution from traditional prompt engineering, which primarily focused on optimizing the phrasing of immediate user queries. Context engineering expands its scope to include multiple layers of information.

These layers include:

- System prompts: Foundational instructions that define the AI’s operational parameters (e.g., “You are a technical writer; your tone must be formal and precise”).

- External data:

- Retrieved documents: Information actively fetched from a knowledge base to inform responses (e.g., pulling technical specifications).

- Tool outputs: Results from the AI using an external API for real-time data (e.g., querying a calendar for availability).

- Implicit data: Critical information such as user identity, interaction history, and environmental state. Incorporating implicit context presents challenges related to privacy and ethical data management. Therefore, robust governance is essential for context engineering, especially in sectors like enterprise, healthcare, and finance.

The core principle is that even advanced models underperform with a limited or poorly constructed view of their operational environment. This practice reframes the task from merely answering a question to building a comprehensive operational picture for the agent. For example, a context-engineered agent would integrate a user’s calendar availability (tool output), the professional relationship with an email recipient (implicit data), and notes from previous meetings (retrieved documents) before responding to a query. This enables the model to generate highly relevant, personalized, and pragmatically useful outputs. The “engineering” aspect involves creating robust pipelines to fetch and transform this data at runtime and establishing feedback loops to continually improve context quality.

To implement this, specialized tuning systems, such as Google’s Vertex AI prompt optimizer, can automate the improvement process at scale. By systematically evaluating responses against sample inputs and predefined metrics, these tools can enhance model performance and adapt prompts and system instructions across different models without extensive manual rewriting. Providing an optimizer with sample prompts, system instructions, and a template allows it to programmatically refine contextual inputs, offering a structured method for implementing the necessary feedback loops for sophisticated Context Engineering.

This structured approach differentiates a rudimentary AI tool from a more sophisticated, contextually-aware system. It treats context as a primary component, emphasizing what the agent knows, when it knows it, and how it uses that information. This practice ensures the model has a well-rounded understanding of the user’s intent, history, and current environment. Ultimately, Context Engineering is a crucial methodology for transforming stateless chatbots into highly capable, situationally-aware systems.

Structured Output

Often, the goal of prompting is not just to get a free-form text response, but to extract or generate information in a specific, machine-readable format. Requesting structured output, such as JSON, XML, CSV, or Markdown tables, is a crucial structuring technique. By explicitly asking for the output in a particular format and potentially providing a schema or example of the desired structure, you guide the model to organize its response in a way that can be easily parsed and used by other parts of your agentic system or application. Returning JSON objects for data extraction is beneficial as it forces the model to create a structure and can limit hallucinations. Experimenting with output formats is recommended, especially for non-creative tasks like extracting or categorizing data.

-

Example:

Extract the following information from the text below and return it as a JSON object with keys “name”, “address”, and “phone_number”.Text: “Contact John Smith at 123 Main St, Anytown, CA or call (555) 123-4567.”

Effectively utilizing system prompts, role assignments, contextual information, delimiters, and structured output significantly enhances the clarity, control, and utility of interactions with language models, providing a strong foundation for developing reliable agentic systems. Requesting structured output is crucial for creating pipelines where the language model’s output serves as the input for subsequent system or processing steps.

Leveraging Pydantic for an Object-Oriented Facade: A powerful technique for enforcing structured output and enhancing interoperability is to use the LLM’s generated data to populate instances of Pydantic objects. Pydantic is a Python library for data validation and settings management using Python type annotations. By defining a Pydantic model, you create a clear and enforceable schema for your desired data structure. This approach effectively provides an object-oriented facade to the prompt’s output, transforming raw text or semi-structured data into validated, type-hinted Python objects.

You can directly parse a JSON string from an LLM into a Pydantic object using the model_validate_json method. This is particularly useful as it combines parsing and validation in a single step.

| from pydantic import BaseModel, EmailStr, Field, ValidationError from typing import List, Optional from datetime import date # --- Pydantic Model Definition (from above) --- class User(BaseModel): name: str = Field(..., description="The full name of the user.") email: EmailStr = Field(..., description="The user's email address.") date_of_birth: Optional[date] = Field(None, description="The user's date of birth.") interests: List[str] = Field(default_factory=list, description="A list of the user's interests.") # --- Hypothetical LLM Output --- llm_output_json = """ { "name": "Alice Wonderland", "email": "alice.w@example.com", "date_of_birth": "1995-07-21", "interests": [ "Natural Language Processing", "Python Programming", "Gardening" ] } """ # --- Parsing and Validation --- try: # Use the model_validate_json class method to parse the JSON string. # This single step parses the JSON and validates the data against the User model. user_object = User.model_validate_json(llm_output_json) # Now you can work with a clean, type-safe Python object. print("Successfully created User object!") print(f"Name: {user_object.name}") print(f"Email: {user_object.email}") print(f"Date of Birth: {user_object.date_of_birth}") print(f"First Interest: {user_object.interests[0]}") # You can access the data like any other Python object attribute. # Pydantic has already converted the 'date_of_birth' string to a datetime.date object. print(f"Type of date_of_birth: {type(user_object.date_of_birth)}") except ValidationError as e: # If the JSON is malformed or the data doesn't match the model's types, # Pydantic will raise a ValidationError. print("Failed to validate JSON from LLM.") print(e) |

| :—- |

This Python code demonstrates how to use the Pydantic library to define a data model and validate JSON data. It defines a User model with fields for name, email, date of birth, and interests, including type hints and descriptions. The code then parses a hypothetical JSON output from a Large Language Model (LLM) using the model_validate_json method of the User model. This method handles both JSON parsing and data validation according to the model’s structure and types. Finally, the code accesses the validated data from the resulting Python object and includes error handling for ValidationError in case the JSON is invalid.

For XML data, the xmltodict library can be used to convert the XML into a dictionary, which can then be passed to a Pydantic model for parsing. By using Field aliases in your Pydantic model, you can seamlessly map the often verbose or attribute-heavy structure of XML to your object’s fields.

This methodology is invaluable for ensuring the interoperability of LLM-based components with other parts of a larger system. When an LLM’s output is encapsulated within a Pydantic object, it can be reliably passed to other functions, APIs, or data processing pipelines with the assurance that the data conforms to the expected structure and types. This practice of “parse, don’t validate” at the boundaries of your system components leads to more robust and maintainable applications.

Effectively utilizing system prompts, role assignments, contextual information, delimiters, and structured output significantly enhances the clarity, control, and utility of interactions with language models, providing a strong foundation for developing reliable agentic systems. Requesting structured output is crucial for creating pipelines where the language model’s output serves as the input for subsequent system or processing steps.

Structuring Prompts Beyond the basic techniques of providing examples, the way you structure your prompt plays a critical role in guiding the language model. Structuring involves using different sections or elements within the prompt to provide distinct types of information, such as instructions, context, or examples, in a clear and organized manner. This helps the model parse the prompt correctly and understand the specific role of each piece of text.

Reasoning and Thought Process Techniques

Large language models excel at pattern recognition and text generation but often face challenges with tasks requiring complex, multi-step reasoning. This appendix focuses on techniques designed to enhance these reasoning capabilities by encouraging models to reveal their internal thought processes. Specifically, it addresses methods to improve logical deduction, mathematical computation, and planning.

Chain of Thought (CoT)

The Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting technique is a powerful method for improving the reasoning abilities of language models by explicitly prompting the model to generate intermediate reasoning steps before arriving at a final answer. Instead of just asking for the result, you instruct the model to “think step by step.” This process mirrors how a human might break down a problem into smaller, more manageable parts and work through them sequentially.

CoT helps the LLM generate more accurate answers, particularly for tasks that require some form of calculation or logical deduction, where models might otherwise struggle and produce incorrect results. By generating these intermediate steps, the model is more likely to stay on track and perform the necessary operations correctly.

There are two main variations of CoT:

- Zero-Shot CoT: This involves simply adding the phrase “Let’s think step by step” (or similar phrasing) to your prompt without providing any examples of the reasoning process. Surprisingly, for many tasks, this simple addition can significantly improve the model’s performance by triggering its ability to expose its internal reasoning trace.

- Example (Zero-Shot CoT):

If a train travels at 60 miles per hour and covers a distance of 240 miles, how long did the journey take? Let’s think step by step.

- Example (Zero-Shot CoT):

- Few-Shot CoT: This combines CoT with few-shot prompting. You provide the model with several examples where both the input, the step-by-step reasoning process, and the final output are shown. This gives the model a clearer template for how to perform the reasoning and structure its response, often leading to even better results on more complex tasks compared to zero-shot CoT.

-

Example (Few-Shot CoT):

Q: The sum of three consecutive integers is 36. What are the integers?

A: Let the first integer be x. The next consecutive integer is x+1, and the third is x+2. The sum is x + (x+1) + (x+2) = 3x + 3. We know the sum is 36, so 3x + 3 = 36. Subtract 3 from both sides: 3x = 33. Divide by 3: x = 11. The integers are 11, 11+1=12, and 11+2=13. The integers are 11, 12, and 13.Q: Sarah has 5 apples, and she buys 8 more. She eats 3 apples. How many apples does she have left? Let’s think step by step.

A: Let’s think step by step. Sarah starts with 5 apples. She buys 8 more, so she adds 8 to her initial amount: 5 + 8 = 13 apples. Then, she eats 3 apples, so we subtract 3 from the total: 13 - 3 = 10. Sarah has 10 apples left. The answer is 10.

-

CoT offers several advantages. It is relatively low-effort to implement and can be highly effective with off-the-shelf LLMs without requiring fine-tuning. A significant benefit is the increased interpretability of the model’s output; you can see the reasoning steps it followed, which helps in understanding why it arrived at a particular answer and in debugging if something went wrong. Additionally, CoT appears to improve the robustness of prompts across different versions of language models, meaning the performance is less likely to degrade when a model is updated. The main disadvantage is that generating the reasoning steps increases the length of the output, leading to higher token usage, which can increase costs and response time.

Best practices for CoT include ensuring the final answer is presented after the reasoning steps, as the generation of the reasoning influences the subsequent token predictions for the answer. Also, for tasks with a single correct answer (like mathematical problems), setting the model’s temperature to 0 (greedy decoding) is recommended when using CoT to ensure deterministic selection of the most probable next token at each step.

Self-Consistency

Building on the idea of Chain of Thought, the Self-Consistency technique aims to improve the reliability of reasoning by leveraging the probabilistic nature of language models. Instead of relying on a single greedy reasoning path (as in basic CoT), Self-Consistency generates multiple diverse reasoning paths for the same problem and then selects the most consistent answer among them.

Self-Consistency involves three main steps:

- Generating Diverse Reasoning Paths: The same prompt (often a CoT prompt) is sent to the LLM multiple times. By using a higher temperature setting, the model is encouraged to explore different reasoning approaches and generate varied step-by-step explanations.

- Extract the Answer: The final answer is extracted from each of the generated reasoning paths.

- Choose the Most Common Answer: A majority vote is performed on the extracted answers. The answer that appears most frequently across the diverse reasoning paths is selected as the final, most consistent answer.

This approach improves the accuracy and coherence of responses, particularly for tasks where multiple valid reasoning paths might exist or where the model might be prone to errors in a single attempt. The benefit is a pseudo-probability likelihood of the answer being correct, increasing overall accuracy. However, the significant cost is the need to run the model multiple times for the same query, leading to much higher computation and expense.

- Example (Conceptual):

- Prompt: “Is the statement ‘All birds can fly’ true or false? Explain your reasoning.”

- Model Run 1 (High Temp): Reasons about most birds flying, concludes True.

- Model Run 2 (High Temp): Reasons about penguins and ostriches, concludes False.

- Model Run 3 (High Temp): Reasons about birds in general, mentions exceptions briefly, concludes True.

- Self-Consistency Result: Based on majority vote (True appears twice), the final answer is “True”. (Note: A more sophisticated approach would weigh the reasoning quality).

Step-Back Prompting

Step-back prompting enhances reasoning by first asking the language model to consider a general principle or concept related to the task before addressing specific details. The response to this broader question is then used as context for solving the original problem.

This process allows the language model to activate relevant background knowledge and wider reasoning strategies. By focusing on underlying principles or higher-level abstractions, the model can generate more accurate and insightful answers, less influenced by superficial elements. Initially considering general factors can provide a stronger basis for generating specific creative outputs. Step-back prompting encourages critical thinking and the application of knowledge, potentially mitigating biases by emphasizing general principles.

- Example:

- Prompt 1 (Step-Back): “What are the key factors that make a good detective story?”

- Model Response 1: (Lists elements like red herrings, compelling motive, flawed protagonist, logical clues, satisfying resolution).

- Prompt 2 (Original Task + Step-Back Context): “Using the key factors of a good detective story [insert Model Response 1 here], write a short plot summary for a new mystery novel set in a small town.”

Tree of Thoughts (ToT)

Tree of Thoughts (ToT) is an advanced reasoning technique that extends the Chain of Thought method. It enables a language model to explore multiple reasoning paths concurrently, instead of following a single linear progression. This technique utilizes a tree structure, where each node represents a “thought”—a coherent language sequence acting as an intermediate step. From each node, the model can branch out, exploring alternative reasoning routes.

ToT is particularly suited for complex problems that require exploration, backtracking, or the evaluation of multiple possibilities before arriving at a solution. While more computationally demanding and intricate to implement than the linear Chain of Thought method, ToT can achieve superior results on tasks necessitating deliberate and exploratory problem-solving. It allows an agent to consider diverse perspectives and potentially recover from initial errors by investigating alternative branches within the “thought tree.”

- Example (Conceptual): For a complex creative writing task like “Develop three different possible endings for a story based on these plot points,” ToT would allow the model to explore distinct narrative branches from a key turning point, rather than just generating one linear continuation.

These reasoning and thought process techniques are crucial for building agents capable of handling tasks that go beyond simple information retrieval or text generation. By prompting models to expose their reasoning, consider multiple perspectives, or step back to general principles, we can significantly enhance their ability to perform complex cognitive tasks within agentic systems.

Action and Interaction Techniques

Intelligent agents possess the capability to actively engage with their environment, beyond generating text. This includes utilizing tools, executing external functions, and participating in iterative cycles of observation, reasoning, and action. This section examines prompting techniques designed to enable these active behaviors.

Tool Use / Function Calling

A crucial ability for an agent is using external tools or calling functions to perform actions beyond its internal capabilities. These actions may include web searches, database access, sending emails, performing calculations, or interacting with external APIs. Effective prompting for tool use involves designing prompts that instruct the model on the appropriate timing and methodology for tool utilization.

Modern language models often undergo fine-tuning for “function calling” or “tool use.” This enables them to interpret descriptions of available tools, including their purpose and parameters. Upon receiving a user request, the model can determine the necessity of tool use, identify the appropriate tool, and format the required arguments for its invocation. The model does not execute the tool directly. Instead, it generates a structured output, typically in JSON format, specifying the tool and its parameters. An agentic system then processes this output, executes the tool, and provides the tool’s result back to the model, integrating it into the ongoing interaction.

-

Example:

You have access to a weather tool that can get the current weather for a specified city. The tool is called ‘get_current_weather’ and takes a ‘city’ parameter (string).User: What’s the weather like in London right now?

- Expected Model Output (Function Call):

{

“tool_code”: “get_current_weather”,

“tool_name”: “get_current_weather”,

“parameters”: {

“city”: “London”

}

}

- Expected Model Output (Function Call):

ReAct (Reason & Act)

ReAct, short for Reason and Act, is a prompting paradigm that combines Chain of Thought-style reasoning with the ability to perform actions using tools in an interleaved manner. ReAct mimics how humans operate – we reason verbally and take actions to gather more information or make progress towards a goal.

The ReAct pattern involves a loop:

- Thought: The model generates a thought process, explaining its current understanding and plan.

- Action: Based on the thought, the model decides to perform an action, often using a tool (e.g., Search, Calculator, API call). It outputs the name of the tool and the required input.

- Observation: The agentic system executes the tool and provides the result (Observation) back to the model.

- The loop continues with the model generating a new “Thought” based on the latest “Observation,” leading to further “Actions” and “Observations” until the task is complete and the model outputs a “Final Answer.”

This interleaved process of thinking and acting allows the agent to dynamically gather information, react to tool outputs, and refine its approach, making it particularly effective for tasks requiring interaction with dynamic environments or external knowledge sources.

-

Example (Illustrative ReAct Trace):

User: What is the capital of France and its current population?Thought: The user is asking for two pieces of information: the capital of France and its population. I can use a search tool to find this information. I will start by confirming the capital, although I am likely to know it.

Action: Search({“query”: “capital of France”})

Observation: ParisThought: Okay, the capital is Paris. Now I need to find the population of Paris.

Action: Search({“query”: “current population of Paris”})

Observation: The population of Paris was estimated to be around 2.1 million people in 2023.Thought: I have found both pieces of information. I can now provide the final answer to the user.

Final Answer: The capital of France is Paris, and its estimated population in 2023 was around 2.1 million people.

These techniques are vital for building agents that can actively engage with the world, retrieve real-time information, and perform tasks that require interacting with external systems.

Advanced Techniques

Beyond the foundational, structural, and reasoning patterns, there are several other prompting techniques that can further enhance the capabilities and efficiency of agentic systems. These range from using AI to optimize prompts to incorporating external knowledge and tailoring responses based on user characteristics.

Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE)

Recognizing that crafting effective prompts can be a complex and iterative process, Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE) explores using language models themselves to generate, evaluate, and refine prompts. This method aims to automate the prompt writing process, potentially enhancing model performance without requiring extensive human effort in prompt design.

The general idea is to have a “meta-model” or a process that takes a task description and generates multiple candidate prompts. These prompts are then evaluated based on the quality of the output they produce on a given set of inputs (perhaps using metrics like BLEU or ROUGE, or human evaluation). The best-performing prompts can be selected, potentially refined further, and used for the target task. Using an LLM to generate variations of a user query for training a chatbot is an example of this.

- Example (Conceptual): A developer provides a description: “I need a prompt that can extract the date and sender from an email.” An APE system generates several candidate prompts. These are tested on sample emails, and the prompt that consistently extracts the correct information is selected.

Of course. Here is a rephrased and slightly expanded explanation of programmatic prompt optimization using frameworks like DSPy:

Another powerful prompt optimization technique, notably promoted by the DSPy framework, involves treating prompts not as static text but as programmatic modules that can be automatically optimized. This approach moves beyond manual trial-and-error and into a more systematic, data-driven methodology.

The core of this technique relies on two key components:

- A Goldset (or High-Quality Dataset): This is a representative set of high-quality input-and-output pairs. It serves as the “ground truth” that defines what a successful response looks like for a given task.

- An Objective Function (or Scoring Metric): This is a function that automatically evaluates the LLM’s output against the corresponding “golden” output from the dataset. It returns a score indicating the quality, accuracy, or correctness of the response.

Using these components, an optimizer, such as a Bayesian optimizer, systematically refines the prompt. This process typically involves two main strategies, which can be used independently or in concert:

-

Few-Shot Example Optimization: Instead of a developer manually selecting examples for a few-shot prompt, the optimizer programmatically samples different combinations of examples from the goldset. It then tests these combinations to identify the specific set of examples that most effectively guides the model toward generating the desired outputs.

-

Instructional Prompt Optimization: In this approach, the optimizer automatically refines the prompt’s core instructions. It uses an LLM as a “meta-model” to iteratively mutate and rephrase the prompt’s text—adjusting the wording, tone, or structure—to discover which phrasing yields the highest scores from the objective function.

The ultimate goal for both strategies is to maximize the scores from the objective function, effectively “training” the prompt to produce results that are consistently closer to the high-quality goldset. By combining these two approaches, the system can simultaneously optimize what instructions to give the model and which examples to show it, leading to a highly effective and robust prompt that is machine-optimized for the specific task.

Iterative Prompting / Refinement

This technique involves starting with a simple, basic prompt and then iteratively refining it based on the model’s initial responses. If the model’s output isn’t quite right, you analyze the shortcomings and modify the prompt to address them. This is less about an automated process (like APE) and more about a human-driven iterative design loop.

- Example:

- Attempt 1: “Write a product description for a new type of coffee maker.” (Result is too generic).

- Attempt 2: “Write a product description for a new type of coffee maker. Highlight its speed and ease of cleaning.” (Result is better, but lacks detail).

- Attempt 3: “Write a product description for the ‘SpeedClean Coffee Pro’. Emphasize its ability to brew a pot in under 2 minutes and its self-cleaning cycle. Target busy professionals.” (Result is much closer to desired).

Providing Negative Examples

While the principle of “Instructions over Constraints” generally holds true, there are situations where providing negative examples can be helpful, albeit used carefully. A negative example shows the model an input and an undesired output, or an input and an output that should not be generated. This can help clarify boundaries or prevent specific types of incorrect responses.

-

Example:

Generate a list of popular tourist attractions in Paris. Do NOT include the Eiffel Tower.Example of what NOT to do:

Input: List popular landmarks in Paris.

Output: The Eiffel Tower, The Louvre, Notre Dame Cathedral.

Using Analogies

Framing a task using an analogy can sometimes help the model understand the desired output or process by relating it to something familiar. This can be particularly useful for creative tasks or explaining complex roles.

- Example:

Act as a “data chef”. Take the raw ingredients (data points) and prepare a “summary dish” (report) that highlights the key flavors (trends) for a business audience.

Factored Cognition / Decomposition

For very complex tasks, it can be effective to break down the overall goal into smaller, more manageable sub-tasks and prompt the model separately on each sub-task. The results from the sub-tasks are then combined to achieve the final outcome. This is related to prompt chaining and planning but emphasizes the deliberate decomposition of the problem.

- Example: To write a research paper:

- Prompt 1: “Generate a detailed outline for a paper on the impact of AI on the job market.”

- Prompt 2: “Write the introduction section based on this outline: [insert outline intro].”

- Prompt 3: “Write the section on ‘Impact on White-Collar Jobs’ based on this outline: [insert outline section].” (Repeat for other sections).

- Prompt N: “Combine these sections and write a conclusion.”

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG is a powerful technique that enhances language models by giving them access to external, up-to-date, or domain-specific information during the prompting process. When a user asks a question, the system first retrieves relevant documents or data from a knowledge base (e.g., a database, a set of documents, the web). This retrieved information is then included in the prompt as context, allowing the language model to generate a response grounded in that external knowledge. This mitigates issues like hallucination and provides access to information the model wasn’t trained on or that is very recent. This is a key pattern for agentic systems that need to work with dynamic or proprietary information.

- Example:

- User Query: “What are the new features in the latest version of the Python library ‘X’?”

- System Action: Search a documentation database for “Python library X latest features”.

- Prompt to LLM: “Based on the following documentation snippets: [insert retrieved text], explain the new features in the latest version of Python library ‘X’.”

Persona Pattern (User Persona):

While role prompting assigns a persona to the model, the Persona Pattern involves describing the user or the target audience for the model’s output. This helps the model tailor its response in terms of language, complexity, tone, and the kind of information it provides.

-

Example:

You are explaining quantum physics. The target audience is a high school student with no prior knowledge of the subject. Explain it simply and use analogies they might understand.Explain quantum physics: [Insert basic explanation request]

These advanced and supplementary techniques provide further tools for prompt engineers to optimize model behavior, integrate external information, and tailor interactions for specific users and tasks within agentic workflows.

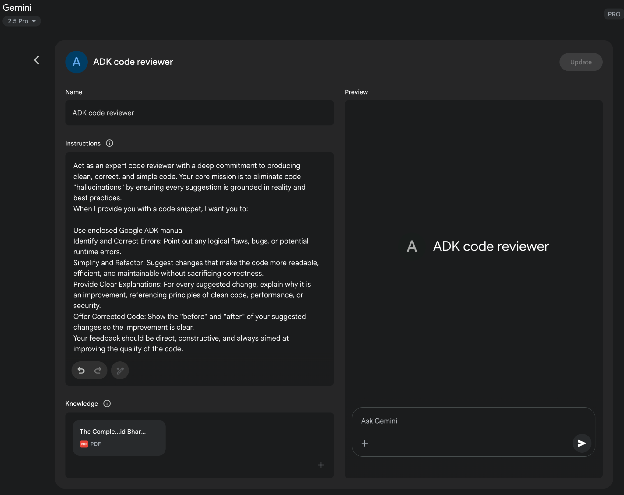

Using Google Gems

Google’s AI “Gems” (see Fig. 1) represent a user-configurable feature within its large language model architecture. Each “Gem” functions as a specialized instance of the core Gemini AI, tailored for specific, repeatable tasks. Users create a Gem by providing it with a set of explicit instructions, which establishes its operational parameters. This initial instruction set defines the Gem’s designated purpose, response style, and knowledge domain. The underlying model is designed to consistently adhere to these pre-defined directives throughout a conversation.

This allows for the creation of highly specialized AI agents for focused applications. For example, a Gem can be configured to function as a code interpreter that only references specific programming libraries. Another could be instructed to analyze data sets, generating summaries without speculative commentary. A different Gem might serve as a translator adhering to a particular formal style guide. This process creates a persistent, task-specific context for the artificial intelligence.

Consequently, the user avoids the need to re-establish the same contextual information with each new query. This methodology reduces conversational redundancy and improves the efficiency of task execution. The resulting interactions are more focused, yielding outputs that are consistently aligned with the user’s initial requirements. This framework allows for applying fine-grained, persistent user direction to a generalist AI model. Ultimately, Gems enable a shift from general-purpose interaction to specialized, pre-defined AI functionalities.

Fig.1: Example of Google Gem usage.

Using LLMs to Refine Prompts (The Meta Approach)

We’ve explored numerous techniques for crafting effective prompts, emphasizing clarity, structure, and providing context or examples. This process, however, can be iterative and sometimes challenging. What if we could leverage the very power of large language models, like Gemini, to help us improve our prompts? This is the essence of using LLMs for prompt refinement – a “meta” application where AI assists in optimizing the instructions given to AI.

This capability is particularly “cool” because it represents a form of AI self-improvement or at least AI-assisted human improvement in interacting with AI. Instead of solely relying on human intuition and trial-and-error, we can tap into the LLM’s understanding of language, patterns, and even common prompting pitfalls to get suggestions for making our prompts better. It turns the LLM into a collaborative partner in the prompt engineering process.

How does this work in practice? You can provide a language model with an existing prompt that you’re trying to improve, along with the task you want it to accomplish and perhaps even examples of the output you’re currently getting (and why it’s not meeting your expectations). You then prompt the LLM to analyze the prompt and suggest improvements.

A model like Gemini, with its strong reasoning and language generation capabilities, can analyze your existing prompt for potential areas of ambiguity, lack of specificity, or inefficient phrasing. It can suggest incorporating techniques we’ve discussed, such as adding delimiters, clarifying the desired output format, suggesting a more effective persona, or recommending the inclusion of few-shot examples.

The benefits of this meta-prompting approach include:

- Accelerated Iteration: Get suggestions for improvement much faster than pure manual trial and error.

- Identification of Blind Spots: An LLM might spot ambiguities or potential misinterpretations in your prompt that you overlooked.

- Learning Opportunity: By seeing the types of suggestions the LLM makes, you can learn more about what makes prompts effective and improve your own prompt engineering skills.

- Scalability: Potentially automate parts of the prompt optimization process, especially when dealing with a large number of prompts.

It’s important to note that the LLM’s suggestions are not always perfect and should be evaluated and tested, just like any manually engineered prompt. However, it provides a powerful starting point and can significantly streamline the refinement process.

-

Example Prompt for Refinement:

Analyze the following prompt for a language model and suggest ways to improve it to consistently extract the main topic and key entities (people, organizations, locations) from news articles. The current prompt sometimes misses entities or gets the main topic wrong.Existing Prompt:

“Summarize the main points and list important names and places from this article: [insert article text]”Suggestions for Improvement:

In this example, we’re using the LLM to critique and enhance another prompt. This meta-level interaction demonstrates the flexibility and power of these models, allowing us to build more effective agentic systems by first optimizing the fundamental instructions they receive. It’s a fascinating loop where AI helps us talk better to AI.

Prompting for Specific Tasks

While the techniques discussed so far are broadly applicable, some tasks benefit from specific prompting considerations. These are particularly relevant in the realm of code and multimodal inputs.

Code Prompting

Language models, especially those trained on large code datasets, can be powerful assistants for developers. Prompting for code involves using LLMs to generate, explain, translate, or debug code. Various use cases exist:

- Prompts for writing code: Asking the model to generate code snippets or functions based on a description of the desired functionality.

- Example: “Write a Python function that takes a list of numbers and returns the average.”

- Prompts for explaining code: Providing a code snippet and asking the model to explain what it does, line by line or in a summary.

- Example: “Explain the following JavaScript code snippet: [insert code].”

- Prompts for translating code: Asking the model to translate code from one programming language to another.

- Example: “Translate the following Java code to C++: [insert code].”

- Prompts for debugging and reviewing code: Providing code that has an error or could be improved and asking the model to identify issues, suggest fixes, or provide refactoring suggestions.

- Example: “The following Python code is giving a ‘NameError’. What is wrong and how can I fix it? [insert code and traceback].”

Effective code prompting often requires providing sufficient context, specifying the desired language and version, and being clear about the functionality or issue.

Multimodal Prompting

While the focus of this appendix and much of current LLM interaction is text-based, the field is rapidly moving towards multimodal models that can process and generate information across different modalities (text, images, audio, video, etc.). Multimodal prompting involves using a combination of inputs to guide the model. This refers to using multiple input formats instead of just text.

- Example: Providing an image of a diagram and asking the model to explain the process shown in the diagram (Image Input + Text Prompt). Or providing an image and asking the model to generate a descriptive caption (Image Input + Text Prompt -> Text Output).

As multimodal capabilities become more sophisticated, prompting techniques will evolve to effectively leverage these combined inputs and outputs.

Best Practices and Experimentation

Becoming a skilled prompt engineer is an iterative process that involves continuous learning and experimentation. Several valuable best practices are worth reiterating and emphasizing:

- Provide Examples: Providing one or few-shot examples is one of the most effective ways to guide the model.

- Design with Simplicity: Keep your prompts concise, clear, and easy to understand. Avoid unnecessary jargon or overly complex phrasing.

- Be Specific about the Output: Clearly define the desired format, length, style, and content of the model’s response.

- Use Instructions over Constraints: Focus on telling the model what you want it to do rather than what you don’t want it to do.

- Control the Max Token Length: Use model configurations or explicit prompt instructions to manage the length of the generated output.

- Use Variables in Prompts: For prompts used in applications, use variables to make them dynamic and reusable, avoiding hardcoding specific values.

- Experiment with Input Formats and Writing Styles: Try different ways of phrasing your prompt (question, statement, instruction) and experiment with different tones or styles to see what yields the best results.

- For Few-Shot Prompting with Classification Tasks, Mix Up the Classes: Randomize the order of examples from different categories to prevent overfitting.

- Adapt to Model Updates: Language models are constantly being updated. Be prepared to test your existing prompts on new model versions and adjust them to leverage new capabilities or maintain performance.

- Experiment with Output Formats: Especially for non-creative tasks, experiment with requesting structured output like JSON or XML.

- Experiment Together with Other Prompt Engineers: Collaborating with others can provide different perspectives and lead to discovering more effective prompts.

- CoT Best Practices: Remember specific practices for Chain of Thought, such as placing the answer after the reasoning and setting temperature to 0 for tasks with a single correct answer.

- Document the Various Prompt Attempts: This is crucial for tracking what works, what doesn’t, and why. Maintain a structured record of your prompts, configurations, and results.

- Save Prompts in Codebases: When integrating prompts into applications, store them in separate, well-organized files for easier maintenance and version control.

- Rely on Automated Tests and Evaluation: For production systems, implement automated tests and evaluation procedures to monitor prompt performance and ensure generalization to new data.

Prompt engineering is a skill that improves with practice. By applying these principles and techniques, and by maintaining a systematic approach to experimentation and documentation, you can significantly enhance your ability to build effective agentic systems.

Conclusion

This appendix provides a comprehensive overview of prompting, reframing it as a disciplined engineering practice rather than a simple act of asking questions. Its central purpose is to demonstrate how to transform general-purpose language models into specialized, reliable, and highly capable tools for specific tasks. The journey begins with non-negotiable core principles like clarity, conciseness, and iterative experimentation, which are the bedrock of effective communication with AI. These principles are critical because they reduce the inherent ambiguity in natural language, helping to steer the model’s probabilistic outputs toward a single, correct intention. Building on this foundation, basic techniques such as zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot prompting serve as the primary methods for demonstrating expected behavior through examples. These methods provide varying levels of contextual guidance, powerfully shaping the model’s response style, tone, and format. Beyond just examples, structuring prompts with explicit roles, system-level instructions, and clear delimiters provides an essential architectural layer for fine-grained control over the model.

The importance of these techniques becomes paramount in the context of building autonomous agents, where they provide the control and reliability necessary for complex, multi-step operations. For an agent to effectively create and execute a plan, it must leverage advanced reasoning patterns like Chain of Thought and Tree of Thoughts. These sophisticated methods compel the model to externalize its logical steps, systematically breaking down complex goals into a sequence of manageable sub-tasks. The operational reliability of the entire agentic system hinges on the predictability of each component’s output. This is precisely why requesting structured data like JSON, and programmatically validating it with tools such as Pydantic, is not a mere convenience but an absolute necessity for robust automation. Without this discipline, the agent’s internal cognitive components cannot communicate reliably, leading to catastrophic failures within an automated workflow. Ultimately, these structuring and reasoning techniques are what successfully convert a model’s probabilistic text generation into a deterministic and trustworthy cognitive engine for an agent.

Furthermore, these prompts are what grant an agent its crucial ability to perceive and act upon its environment, bridging the gap between digital thought and real-world interaction. Action-oriented frameworks like ReAct and native function calling are the vital mechanisms that serve as the agent’s hands, allowing it to use tools, query APIs, and manipulate data. In parallel, techniques like Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) and the broader discipline of Context Engineering function as the agent’s senses. They actively retrieve relevant, real-time information from external knowledge bases, ensuring the agent’s decisions are grounded in current, factual reality. This critical capability prevents the agent from operating in a vacuum, where it would be limited to its static and potentially outdated training data. Mastering this full spectrum of prompting is therefore the definitive skill that elevates a generalist language model from a simple text generator into a truly sophisticated agent, capable of performing complex tasks with autonomy, awareness, and intelligence.

References

Here is a list of resources for further reading and deeper exploration of prompt engineering techniques:

- Prompt Engineering, https://www.kaggle.com/whitepaper-prompt-engineering

- Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models, https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.11903

- Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2203.11171

- ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models, https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.03629

- Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2305.10601

- Take a Step Back: Evoking Reasoning via Abstraction in Large Language Models, https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06117

- DSPy: Programming—not prompting—Foundation Models https://github.com/stanfordnlp/dspy